Hearing history’s song

Hearing history’s song

BSC Prof. Lester Seigel ’79 shares research on the Birmingham Conservatory of Music’s storied past

There’s a lot of hidden history in the Hill Music Building at BSC.

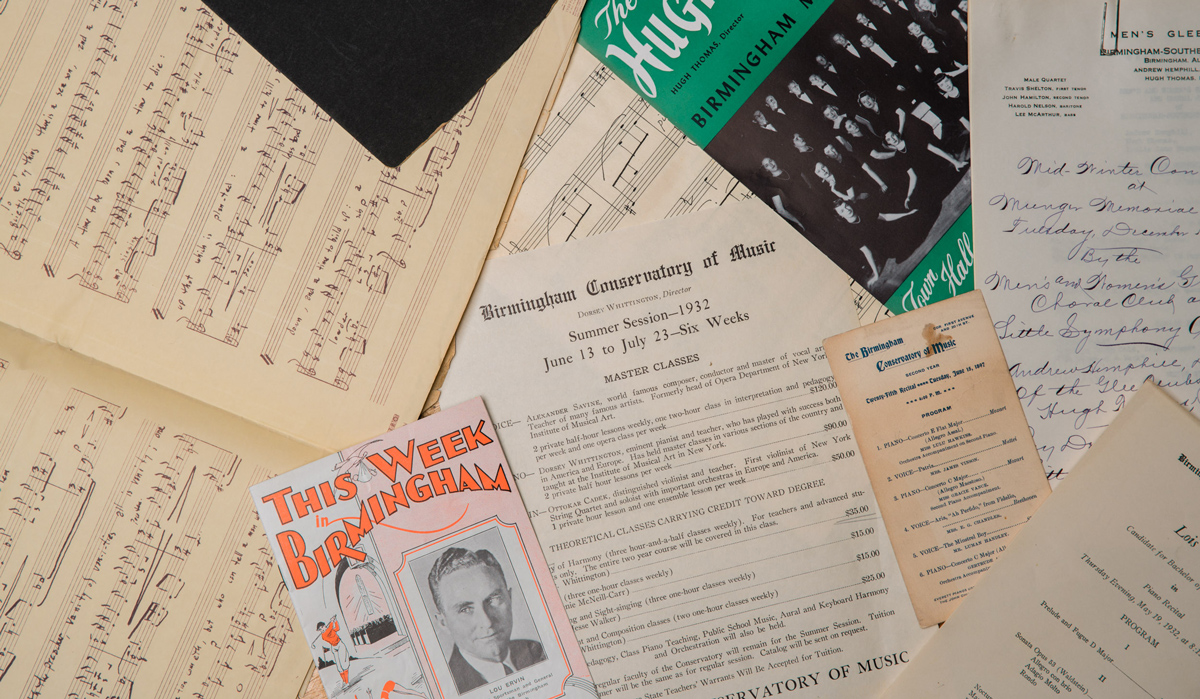

Some of it really was hidden – tucked away in the bottom drawer of a file cabinet in the choral library. That is, until Music Professor Dr. Lester Seigel ’79 found a cache of old photographs, sheet music, and more and decided it was time to take a closer look.

Seigel spent his recent sabbatical researching the Birmingham Conservatory of Music, which was absorbed into BSC in the 1950s and boosted the college’s regional and national reputation for music education. The conservatory also played a big role in the city’s musical past, Seigel found.

“It was linked to the individuals and the institutions that were the drivers of professional classical music in Birmingham,” Seigel said. “And Birmingham was a player in those days.”

Seigel presented some of his discoveries at a Provost’s Forum on Nov. 6 on campus. Titled “Who Stole My Waltz? Tales of the Birmingham Conservatory of Music,” the talk included glimpses into the glittering past of music on the Hilltop and downtown, along with a performance of music composed by Conservatory artists.

“I have said there’s an historian in me that’s dying to get out,” Seigel said. “This was a shot at doing some real historical work.”

The conservatory, founded downtown in 1895, became a cultural icon as Birmingham’s fame and wealth grew around the turn of the century. It moved several times, landing in the 1920s in its own building across from Phillips High School on 7th Avenue North, with studios, offices, reception rooms, and a 300-seat recital hall.

Seigel traces the history from its initial founder, Benjamin Guckenberger, through Dorsey Whittington, who took over in 1930, and beyond. Under Whittington’s leadership, the conservatory moved to the BSC campus in 1940, enlarging the college’s musical footprint. In those days, students would earn an undergraduate degree in music from the college and a master’s degree from the conservatory.

The two institutions operated independently but cooperatively until 1953, when the conservatory merged into the college’s music department and became the Birmingham-Southern College Conservatory of Fine and Performing Arts.

In a way, the project is more than just a labor of love – it’s a genealogical study. Seigel said that musicians love to trace their own lineage through their teachers, which certainly applies here.

Seigel studied for eleven years with Conservatory and BSC alumna Lois Greene Seals ’28, starting at the age of 5. In high school, his teacher was Joseph Hugh Thomas ’33, the choral conductor and pianist who was dean of the BSC Conservatory (where he earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree, in addition to his A.B. from BSC) in the 1950s, and chair of BSC’s Music Department from 1964-72. Seigel carries the title of Joseph Hugh Thomas Professor of Music, as well as being chair of the department and the conductor of BSC’s main choral ensembles, including the Concert Choir that Thomas co-founded.

Both Seals and Thomas, in turn, studied with Whittington, who traced his own teaching tree back to Clara Schumann, the 19th century German concert pianist and composer who was married to composer Robert Schumann. Whittington and his wife, Frances, are honored by the college’s annual Whittington Music Competition, in which students earn a chance to perform with a professional orchestra.

There are other connections as well. Guckenberger, the conservatory’s first director, filled the role of choir director at Birmingham’s Temple Emanu-El – a role Seigel himself also held before coming to Birmingham-Southern. Edna Gockel Gussen, who was the conservatory’s first graduate and third director, also worked at the temple and wrote the music for “Alabama,” the state’s official song, setting Julia Tutwiler’s poem to music in 1931.

That musical and historical connectivity may explain why Seigel can so clearly picture Birmingham’s musical heyday, when stars like Vladimir Horowitz performed for the Birmingham Music Club and nationally renowned composers created works on behalf of local institutions.

He’s especially excited to share sheet music and songs, including “Chant Nuptiale,” a piece for cello and piano written by conservatory teacher G. Ackley Brower for the wedding of Hugh Thomas and fellow teacher Barbara Dorough Thomas ’37. And there are a few mysteries still unsolved, including unidentified portraits of musicians that were included in the files, and just what will become of the downtown conservatory building.

Meanwhile, Seigel plans to keep digging through the historical record and working to publish his results.

“The Birmingham Conservatory really is an example of these conservatories that sprang up like mushrooms in small to mid-sized cities across the U.S. after the Civil War,” Seigel said. While initially designed to teach young society ladies the musical arts, they formed a broader base of musical education and many – like BSC’s, Oberlin College’s, and others – were absorbed into higher education.

Today, the conservatory has returned to its original roots of classical music education for K-12 students on the BSC campus. It claims such famous alumni as Hugh Martin, the composer of the score of Meet me in St. Louis, (including “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”), and former U.S. Secretary of State Condolezza Rice, who took piano there as a teen.

“In an interesting way, it’s back to where it started,” Seigel said.